The Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata is considered to be an important text in the political theorisation in ancient India. The Shanti Parva discusses important topics such as Sovereignty, Origin of the State, Powers and duties of the King, rules and ethics of ruling, duties of the citizens etc., Shanti Parva is also important because it gives some understanding of how socio-political thinking in India is different from other societies and why is it necessary to revisit that theorisation.

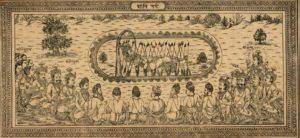

Political Ideas in the Shanti Parva are in the form of discourses given by Bhishma, the grandsire of the Kauravas and Pandavas to Yudhishthira after the great war is over. The Shanti Parva is the 12th of the 18 parvas of the Mahabharata. The Shanti Parva consists of three upa parvas or sections- Rajdharmanushasana Parva, Apaddharma Parva, and Mokshadharma Parva and contains 365 chapters in all. It is the longest amongst the 18 parvas of the great epic. The first upa parva deals with politics and ethics, the second with Dharma in the time of distress, and the third deals with lessons on attainment of Moksha (renunciation). The discussion on politics and actual Rajadharma begins from the 56th Chapter. In the Mahabharata, Rajadharma is considered as the most important science. Rajadharma is also referred to as Kshatra-Dharma. In fact, the Shanti Parva regards Rajadharma as the root of all dharmas[1].

However, the Shanti Parva is not the first discussion on political ideas in ancient India, though it is one of the oldest and contains a descriptive discussion on the same. There are references to various predecessors of political thinking in the Shanti Parva. For example, the Shanti Parva mentions the 7 important treatises of Statecraft that are attributed to Bharadavaja, Vishalaksha, Parashara, Pishuna/Narada, Kaunapadanta/Bhishma, Vatavyadhi and Bahudantin/Mahendra, and it makes an addition to it by mentioning Gaurishiras[2].

Thus, in order to understand the nature of political theorisation in the Shanti Parva, it is necessary to have a basic understanding of certain important predecessors of the Shanti Parva theorisation.

Political Ideas in Ancient India:

The Vedas are the oldest treatises of knowledge in India. They contain ideals for both the king and the citizens necessary for ensuring a peaceful and harmonious society. Ashok Chousalkar in his ‘Methodology of Kautilya’s Arthashastra’ mentions that in ancient India, the science of politics was called ‘Drishtartha’ and was based on the ‘fifth Veda’ called ‘Itihasa’ and suggests the interpretation of the world which was visible to the senses.

When the five organisations of the Vedic society, namely Gotra, Grama, Visha, Jana and Rashtra were combined, political developments in the Vedic period are said to begin[3]. Some scholars like Bandyopadhyay believe that initially grama was the smallest unit and the jana was the highest political unit. Various other scholars place importance to the role of grama in political unification of the people, and eventually concepts like Rashtra and Rajya became important as the highest political unit. Rashtra was monarchical in nature. There are also references to ‘ganas’ or republics in Rigvedic literature. There are also many names associated with the Rashtra in the Vedic literature. The chief of the Vedic Rashtra is sometimes referred to as ‘antarbhu’, meaning, he was one of the visas and was considered as the most civilised person within the society. There are mentions of the process of choosing the king, which was performed by the rajakrita and gramina. The Atharva Veda mentions the processes of choosing the king. We can thus find various attributes attached to the conduct of a king, process/rationale behind ousting a king, re-electing an apparently driven out king etc.,

In the Vedic literature, the concepts of Dharma and Danda become important in the realm of political ideas. In the Vedic literature, we find the term ‘Rit or ‘Rta’ in place of Dharma at some instances. Rit/Rta, in short, is the natural order of the universe and the laws that govern it; it manifests and presents the stable, established system of the material and moral elements. As time passed, Rit/Rta earned a stronger moral effect and its violation was considered a sin, and its moral significance was later attached to Dharma. Rta/Rit formed the epicentre or the duty of the Vedic Politics. The Kshatra or Kshatrasri were the Rigvedic terms synonymous to the Political Sovereign and politics was thus called Kshatra or Kshatri. The sovereignty depended on the king. These moral connotations attached to the State, King, and the overall political set-up show a strong influence on Shanti Parva’s theorisation of the State and its functions.

An initial enquiry into these predecessors of the Shanti Parva reveals to us certain important aspects of the nature of politics and political theorisation in ancient India. First, the moral connotations attached to the institution of the State and King. Second, this moral connotation can be said to have been translated into the doctrine of ‘Dharma,’ and finally, the central stage that Dharma assumes in the complete theorisation. Therefore, Dharma (through Rit/Rta) eventually started forming the epicentre of politics. This can potentially reveal to us the raison d’etat of the State, that is protection and upholding of Dharma in the society.

Since the institution of State is attached to the doctrine of Dharma, the attributes of the King, conduct of the King and citizens, the State-Individual relationship and Power Dynamics of ancient Indian political setup become important aspects of political theorisation.

These aspects can be treated as the intellectual context of the Shanti Parva. The rationale behind the origin of the State and the political ideas associated with the narratives of the origin of the State show resemblance to these Vedic political values.

This article series will attempt to analyse the important political ideas such as State-Individual relationship, Human Nature, Power Dynamics in ancient Indian society, and the raison d’etat of the State, described in Chapters 59 and 67 of the Shanti Parva that deal with the theories of Origin of State. We will also try to understand how the Indian understanding of certain fundamental political ideas is different from that of the West.

In the next article, we will try to analyse the narratives regarding theories related to the origin of the State in the Shanti Parva and how they form the backdrop of certain foundational political ideas and values.

References

Vyasa, V. (n.d.). Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyas Translated into English prose from the original Sanskrit text (Vols. VIII, Shanti Parva Part 1). (P. C. Roy, Trans.) Kolkata: Oriental Publishing Company

Garg, S. (2004). POLITICAL IDEAS OF SHANTI PARVA. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 65(1), 77–86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41855798

Mishra, K. K. (2004). THE STUDY OF ANCIENT INDIAN POLITICAL TRADITIONS. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 65(1), 9–20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41855793

Pandey, P. (2019). Rajdharma in Mahabharata with special reference to Shanti Parva. New Delhi: D. K Printworld.

[1] Shanti Parva 2LXIII 25,26,29; CXLI 9-10; LVI 3

[2] The Study of Ancient Indian Political Traditions, by Kaushal Kishore Mishra in the Indian Journal of Political Science (Volume 65; Jan-March 2004), page 11.

[3] Political Ideas in Shanti Parva, in ‘Rajdharma in Mahabharat with special reference to the Shanti Parva’ by Dr. Priyanka Pandey.

Author : Sameeran Galagali

Sameeran is a under-gruadate student in Political Science at S.P College, Pune. Sameeran was also selected as a participant in the MFIS Study Circle on “Studying Socio-Political Thought in Indian Context” and worked on the the same topic as a part of his project.

0 Comments