One of the most fundamental concepts in western political thought is the origin of the institution of State. The West has had its intellectual journey from the ancient Greeks who called man a ‘political animal by nature’ thus implying the State to be a natural institution, to the middle-ages where the State was considered to be of Divine Origin, and to the modern era when the theories of Divine and Natural origin of the State were disbanded, and the State was established as a consciously created institution, implying some sort of contracts among the people. The social contractualist tradition with philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau are of immense importance while talking about the modern theories of origin of state, and other political ideas such as human nature, raison detat of the State, Political Obligation, political consciousness, rights of the ruler and of the citizens amongst others. These ideas in Europe emerged through centuries long intellectual, socio-political context shaped by certain decisive events and revolutions.

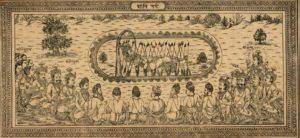

The Shanti Parva, too, has descriptions and theories about the origin of the State, the nature of the state, the duties of the state etc., However, these ideas in the Shanti Parva have emerged centuries before the West started theorising. Therefore, it is necessary to look at these political ideas in the socio-political and intellectual context in which the Shanti Parva had emerged. We have tried to acquire a brief idea of this context in the previous article.

The Shanti Parva treats the State as an extremely critical institution that is necessary to uphold Dharma. Important ideas such as how the State emerged in a pre-political society, how the people gained political consciousness, how do the ruler and citizens perceive each other, ideas about human nature etc., are discussed at length in the Chapters 59 and 67 of the Shanti Parva which deal with the theories related to the origin of the State.

In this article, we will look at both the narratives and in the next article we shall try to understand why do we have two theories on the same concept, and how they help in understanding political theory of Shanti Parva.

I have referred to Prashant Chandra Roy’s translation of the Shanti Parva throughout my reading, therefore, any reference to the Shanti Parva text shall be referred to ‘Mahabharata of Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa; translated into English prose from Original Sanskrit Text by Prashanta Chandra Roy; Volume VIII Shanti Parva (Part 1).’

Chapter 59:

The Chapter 59 of the Shanti Parva can be broadly studied in two parts. First, the Origin of Dandaniti and second, the narrative about the origin of the State. Dandaniti is one of the terms that was used in ancient India to denote the knowledge of politics. The word ‘dandniti’ is made up of two words- ‘dand’ and ‘niti.’ Dand denotes a staff, or punishment aimed at driving off evils that disrupt social harmony and ‘niti’ denotes the science of guiding the ruler to punish the wrong-doers in order to ensure harmony in the society. Dandniti is identified as Rajdharma; it is not only the science related to punishing the wrong-doer, it is in fact treated as a means to achieve social harmony defined in various ways. Dandniti is mentioned in various chapters in the Shanti Parva.

The Shanti Parva describes the pre-political phase of human society, which is also described as the ‘Golden Age’ wherein people lived righteously in the society without any monarch or State. However, after a certain period of time, people started losing their virtues and forgot the path of dharma. Bhishma gives a logical sequencing of how the society degenerated.

Men became covetous, they started acquiring objects that did not belong to them, they got trapped by lust, lust led to anger and greed and this led to a complete state of disorder and anarchy. The Vedas disappeared with righteousness and chastity. Thus, the Gods were taken by fear and approached Brahma, the creator God. Brahma thought over the matter and was convinced that man cannot live in society harmoniously without a codified law enforced by a ruler. Thus, Brahma, on the request of Gods established law and order and created the dandniti, the science of punishment/chastisement. Hence, the science of politics came into existence. The Dandaniti can be more appropriately called ‘the science of chastisement;’ Bhishma says that chastisement leads or governs everything and thus the treatise which Brahma created is the ‘Science of Chastisement.’

After the Dandaniti was created, the Gods approached Vishnu and requested to appoint a King to rule the masses. Vishnu created Virajas, but Virajas refused to take over the reign because he was inclined towards the attainment of moksha. Vena, one of Virajas’ descendants became the King. He was completely possessed by his passions, disrespected dharma and was unrighteous towards all the creatures in conduct. The rishis ousted him and killed him through the power of their mantras. Vena’s right arm was churned and out of that the king Prithu was born. Prithu was well acquired with the knowledge of the Vedas, war and weapons, and the knowledge of dandniti. He promised the Rishis that he will always abide by dharma and the dandniti as a ruler of the mortals. He was thus anointed as the King by the Gods and the Sages. Vishnu entered the body of Prithu and declared that nobody shall transcend him. He was thus offered the divine worship. Prithu was called the ‘Rajan.’

Chapter 67:

The 67th Chapter opens with Yudhishthira asking Bhishma about the principal duties of any kingdom.

The importance of righteousness and dharma is reflected strongly in the 67th Chapter also. While answering Yudhishthira’s question, Bhishma strongly mentions that a State of Anarchy is the worst and thus the first duty of any kingdom is the (election and) coronation of a King, because in a state of anarchy, righteousness cannot be protected, and nobody shall dwell in such states. Bhishma says that a powerful person is necessary to avoid the state of anarchy. When there is State of Anarchy, men once again become covetous, lose chastity, forget righteousness and do not perform their duties rightfully. Here, ‘again’ denotes the state of human relations described in the pre-political phase of society in Chapter 59. Bhishma says that whenever someone commits something unfair to someone, the victim looks upon the King, because the King is believed to be able to deliver justice. This signifies that the King is not just an installed divine authority, but he is vested with the responsibility of delivering justice and ensuring welfare of his citizens. This section of the Shanti Parva seems to make the purpose of the institution of the King/State clearer- the protection of righteousness and avoid a state of anarchy.

The necessity for a king is laid down first by explaining how a state without an authority accepted by the citizens lead to deterioration of human relations.

In this context, Bhishma provides another narrative about the origin of State. Bhishma talks about a society (before the emergence of State/King) where ‘Matsyanyaya’ prevails. In such a society, men who are strong overpower the weak, snatch things which do not belong to them, lose their chastity towards women and human relations begin to degenerate. In the Matsyanyaya, the human relations were such that it became very difficult to carry out the daily state of affairs.

To improve the situation, the people made an agreement amongst themselves that they would keep a conduct of chastity and righteousness towards each other. However, this agreement did not work out. Therefore, the people went to Brahma and requested him to appoint a ruler over them to ensure social peace and protection of Dharma. They had realised that they could not manage their state of affairs on their own and required someone to rule over them. Brahma asked Manu to take the charge as the King of the mortals. Manu, however, rejected saying that it is extremely difficult to rule men because they are extremely deceitful and covetous by nature. Manu finally agreed to rule when the ‘Inhabitants of the Earth’ decided to offer him a portion of their incomes as their worshipping, and in turn he would protect the men. This “protection” more importantly denotes protection of righteousness and chastity. Thus, the protection of dharma meant safeguarding the interests of all.

This narrative clearly states that the institution of Kingship came into existence in the form of an agreement.

A prima facie enquiry into both the narratives make it clear that though both the chapters describe the (Mukherjee, 2021)same concept, they have distinct characters. These distinct characters seem to arise from the differing nature of the contracts mentioned in both the chapters. In the next article, we shall try to understand this differing nature of the narratives and how they pave way for understanding the various facets of political theorisation in the Shanti Parva.

References

Vyasa, V. (n.d.). Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyas Translated into English prose from the original Sanskrit text (Vols. VIII, Shanti Parva Part 1). (P. C. Roy, Trans.) Kolkata: Oriental Publishing Company

Pandey, P. (2019). Rajdharma in Mahabharata with special reference to Shanti Parva. New Delhi: D. K Printworld.

Mukherjee, J. (2021, July 21). Module 14; Political Philosophy in the Mahabharata. Swayam. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/mwnjRF7GzwY?feature=shared

Mukherjee, J. (2021, July 21). Module 15; The Shantiparva: origin and Nature of state . Swayam. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/5yiXMQuj2Qc?feature=shared

Mukherjee, J. (2021, July 21). Module 16; Rajdharma in Shantiparva. Swayam. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/3iMzXRbmj8c?feature=shared

Author : Sameeran Galagali

Sameeran is a under-gruadate student in Political Science at S.P College, Pune. Sameeran was also selected as a participant in the MFIS Study Circle on “Studying Socio-Political Thought in Indian Context” and worked on the the same topic as a part of his project.

0 Comments