Read Part 1 of the Article here.

Archaeological evidences-

There are many Satī stones and inscriptions which mention Satī. One of the earliest is the Gupta age inscription dating to 510 C.E. These and such references tell us that by this age, which is approximately the Gupta Era (4th-5th Century C.E.), Satī was quite commonly practiced in the society.

Most of the inscriptions mention the Satī of women from royal families or the wives of ministers of the king. Needless to say that after the death of king and his men, their women were captured and used as slaves.[1] Kane (1941: 630) states that the practice of Satī was initially limited to the Royal families and was then adapted to by the Brahmana community. This may also indicate that initially even the Brahmana community practiced Satī along with other communities of society. We find quotations of Aṅgīrasa etc. who condemn the practice of Satī for Brahmana-s but consider it as a duty of women of other castes[2].

In other words, Satī was followed by Kshatriya-s, then adapted by Brahmana-s and other castes. But eventually the Brahmana community was asked not to practice it.

Historical references-

Ramabhai, the wife of Mādhavrāo Peshwe chose to die after his death but her mother-in-law lived long after the death of her husband, Nānāsāheb Peshwe. Queen Ahilyabai Holkar led the troops of Maratha empire after the death of her husband.[3]

Until now, it is established that Satī existed in society on a very small scale and it was by late 4th Century C.E., where the probability of the increase in the scope/practice of this custom increased. The inscriptions dating to 5th Century C.E. and later mention the practice of Satī. The practice was not encouraged up to 1000 C.E.[4]

Possible causes of the practice of Satī in later period-

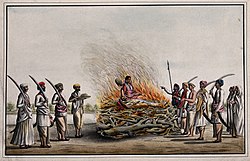

The most commonly given reason for this increase is the contact with invaders. Although it is true to a great extent, there are other minor additional causes as well. Śaṅkha and Aṅgīrasa say that she who follows her husband after his death lives in the heaven for as many years as there are hair on the human body.[5] Further, it is stated that by clasping him and dying in the fire, she gets rid of his sins and she is freed from being born as a woman only after burning herself in fire. She who dies with her husband purifies the family of her mother, father and husband, says Harita. The Mitākṣara quotes these people and then says that the woman should die, irrespective of their castes unless they are pregnant or have small kids at the time of the death of their husbands. Old commentators like Medhātithī said that this practice is nothing but a suicide and forbidden to women. The actions of a woman who does this are aśāstrīya. He even refers to a Vedic quote which contradicts the very action of suicide.[6]

Even the life as a widow was not an easy one. The woman had to depend on the rest of her family and had to be maintained. There were possibilities of being subjected to the assault by other men along with other day to day restrictions of not eating salt, honey etc., not wearing dyed clothes, being celibate and abstaining senses.[7]

Conclusion

Although the custom did not have a sanction by Vedas, the greatness associated with a woman who sacrificed herself like this may have been an important factor to contribute to the rise. The possibility of assault, the difficult life as a widow may have encouraged women to accept Satī.[8] The custom may have become compulsory as the need to protect women from invaders faced by the contemporary society. As seen previously, the life of a slain warrior’s widow can be extremely difficult, particularly if she is captured by an enemy. Hence the option of Satī seemed to have been favored over life as a widow. Kane (1941: 624) points out

´The burning of widows … owes its origin to the oldest religious views and superstitious practices of mankind in general.”

One may conclude that the origin of this custom is not clear and a particular text or community should not be blamed for the same. It was the situation which was initially of a voluntary nature, later discouraged, then was eulogized. This custom was encouraged to protect the honor of women

—————————————————————————————————————————–

[1] This practice is referred to by Harṣa’s mother in the Harṣacarita (chapter 5)

आपीतौ युष्मद्विधैः पुत्रैरमित्रकलत्रबन्दीवृन्दविधूयमानचामरमरुच्चलचीनांशुकधरौ पयोधरौ |

[2] या स्त्री ब्राह्मणजातीया मृतं पतिमनुव्रजेत् सा स्वर्गामात्मघातेन नात्मानं न पतिं नयेत् | (Kane p. 627)

[3] There are rarely any references of common people. These are references only of royal families.

[4] Jain (2016:12)

[5] तिस्रः कोट्यर्धकोटी च यानि लोमानि मानुषे | तावात्कालं वसेत्स्वर्गं भर्तारं यानुगच्छति |

[6] ‘One should not leave this world before one has finished the allotted span of life.’ (Kane 1941: 632)

[7] A virtuous wife who after the death of her husband constantly remains chaste, reaches heaven, though she has no son, just like those chaste men. (The Manusmr̥ti 5.160)

[8] There are instances in the Rājataraṅgiṇī with description of Satī. One instance is where the queen decides to commit Satī but then regrets it and chooses to return.

राज्ञः सुतार्पणाद्धवैरातस्थौ पुरा यतः ।

पतिवत्न्येव सा सार्धं फल्गुणेनाग्र्यमन्त्रिणा ॥ 6.194

पत्यौ मृते सपत्नीनां दृष्ट्वानुमरणं2 ततः ।

दम्भेनानुमुमूर्षन्तीमनुमेने स तां द्रुतम् ॥ 6.195

निषिषेधानुबन्धात्तु सानुतापां चितान्तिके ।

कृपालुर्मरणादेताममात्यो नरवाहनः ॥ 6.196

Previously, while her husband was alive, she had been in enmity with Phālguna, the prime minister, on account of the daughter which he had given in marriage to the king. Hence, out of malice he gave a quick assent when on her husband’s death she wished to become a Satī, seeing other wives [of the king] ready to immolate themselves. But in front of the funeral pyre, she felt regret, and the minister Naravāhana, moved to compassion, prevented her by persistent remonstrances from seeking death.

Views expressed in the article are of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official position of Mimamsa Foundation for Indic Studies.

Author : Jui Mande

Jui Mande wrote this article during her internship at MFIS.

0 Comments