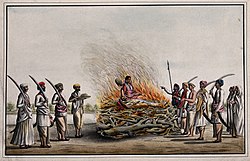

Hindu culture is heavily criticized for the custom of Satī. While, it was considered to be deeply rooted in the society, the origin of this practice is however a contested issue. This article attempts to find reference to this custom to trace its possible origin and the scope.

The concept of a widow burning herself on the pyre of her husband is known by terms such as satī, sahagamana, anvārohaṇa, sahamaraṇa[1]. The term Satī has connotations of truthfulness, virtuousness or righteousness. So, she who is on the virtuous path is Satī[2]. The term anvārohaṇa refers to the action of the widow stepping upon the pyre following her husband. The word sahagamana means going together with (the husband) and sahamaraṇa means dying with (the husband).

There is a little reference to no reference that tells us why the practice was termed as Satī. The texts where this practice is referred to, do not use the term Satī. But other terms mentioned above are found in such texts.[3]

There is a story of Satī, a wife of Lord Śiva that is traditionally narrated with reference to a noble wife. This story which is found in the Mahābhārata (Śāntiparvan), classical Sanskrit literature (the Kumārasaṁbhava) and the Purāṇa-s narrates how Satī immolated herself in fire when Lord Śiva was humiliated by her father Dakṣa. While, it is true that the death of Satī was due to burning, still two notable differences in this action and what was until recent history practiced under the concept of Satī are-

1) the Satī in the story did not die because of the death of her husband. Lord Śiva was alive even after her death and later married the reincarnation of Satī, Pārvatī.

2) self-immolation was absolutely voluntary action on the part of Satī. She was not forced by any custom or person to mark the end of her life.

References to the practice of Satī-

To establish the authority/validity of a practice, it’s origin is traced back to some Vedic hymn, tradition or story that is commonly accepted by the community. If one wishes to establish the practice of Satī as a valid ritual, its origin needs to be linked with Vedas. And such a linkage is found to be stated with the following Vedic hymn.

इ॒मा नारी॑रविध॒वाः सु॒पत्नी॒राञ्ज॑नेन स॒र्पिषा॒ सं वि॑शन्तु ।

अ॒न॒श्रवो॑ऽनमी॒वाः सु॒रत्ना॒ आ रो॑हन्तु॒ जन॑यो॒ योनि॒मग्रे॑ ॥ (10.18.7)[4]

In her book ‘Satī Evangelicals, Baptist Missionaries and the changing Colonial Discourse’ (2016), Meenakshi Jain says that the last part of this Ṛgvedic hymn was interpolated where ‘योनि॒मग्रे॑’ was read as ‘योनि॒मग्ने॑’. As a result, the widow was asked to enter the womb of fire.

But this interpretation due to interpolation is incorrect if the context of this stanza is taken into consideration. The stanza does not refer to widows. It refers to women whose husbands are alive and who are present where the ritual of the deceased man is being performed. The widow is expected to ascend the pyre before it is set ablaze. The married women then ask her to return to the world of mortals as the husband next to her is dead. Then she comes back. The stanza immediately after the one quoted above thus reads as the following,

उदी॑र्ष्व नार्य॒भि जी॑वलो॒कं ग॒तासु॑मे॒तमुप॑ शेष॒ एहि॑ ।

ह॒स्त॒ग्रा॒भस्य॑ दिधि॒षोस्तवे॒दं पत्यु॑र्जनि॒त्वम॒भि सं ब॑भूथ ॥ (10.18.8)[5]

Mahamahopadhyaya P. V. Kane, in his book ‘History of Dharmaśāstra (Vol II) (1941: 625)’ clarifies,

“There is no Vedic passage which can be cited as incontrovertibly referring to widow-burning as then current, nor is there any mantra which could be said to have been repeated in very ancient times at such burning nor do the ancient Gr̥hyasūtras contain any direction prescribing the procedure of widow burning.”

References in epics, the Dharmasūtra and the Smr̥ti texts-

While the references to Satī are found in the Mahābhārata (eg. Mādrī), the Purāṇa-s (eg. Satī), it may not have been as common and certainly not forced upon women.

The killing of women in general was looked down upon, argues Kane (1941) as he discusses the matter of Satī. The Ādiparvan of the Mahābhārata[6] contains references which state that the women are not to be killed. Even the texts that are commonly considered as an authority on Dharma condemn the killing of women[7]. There were certain offences for which women were sentenced to death. But even the king who gave such order had to undergo penance for ordering to kill a woman.[8]

There is one reference in the Viṣṇu Dharmasūtra that says that the widow may follow the celibacy or the anugamana. The texts that are considered as an authority on Dharma viz. the Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra[9], the Gautama Dharmasūtra, the Manusmr̥ti and the Yājñavalkyasmr̥ti do not have reference to Satī. They not only condemn the killing of women but also state that they need to be taken care of by their family members after their husband is dead. The Mitākṣara, the commentary on the Yājñavalkyasmr̥ti has reference to Satī, but is a later addition compared to the previous and more authentic texts.[10] Quotations given by Aparārka[11] have some sūtrakara-s supporting the custom. The similar quotations are found in the Mitākṣara in support of the custom.

However, it is to be noted that there are very few authoritative texts which mention Satī. And even fewer consider Satī as a compulsory duty of women.

The Mahābhārata has rarely any reference. For instance, in the Mahābhārata, Mādrī (mother of Nakula and Sahadeva) chose to die but Kuntī (mother of Yudhiṣṭhira, Bhīma and Arjuna) chose to live after the death of their husband, Pāṇdu. While, some wives of Kṛshna chose the practice of Satī after his death. While, another wife, Satyabhāmā chose to retire to the forest. Further, in the Strīparvan of the Mahābhārata, there is a description of the pyres of dead soldiers and the lamentation of their widows. There is no mention of Satī in this section.[12]

The references that are claimed to be connected to Satī are rare and confined mostly to the royal families as found to be described in these texts. The presence of Satī is undeniable but rare. In other words, it can be said that it was a fairly uncommon practice and was out of choice for women.

References in other literature-

The Kumārasaṁbhava (Canto 4) has Rati’s desire to die after her husband (Madana) is burnt by Śiva. But, the voice from sky stops her from committing Satī and convinces her to retain her body.[13]

The Gathāsaptaśatī (7.33) has a similar indication of a woman willing to commit Satī but is prevented from doing so.[14] Such a reference points out that Satī may not seem to have been confined to the royal families.

Further, there is reference to Satī in the Harṣacarita where Harṣa’s mother immolates herself. Except here, she does so before the death of her husband.[15] In the Kādambarī, Bāṇabhatta condemns the practice of Satī.[16] While, the Rājataraṅgiṇī has comparatively more references to Satī of common people.[17]

Among foreign records, there are records of Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo who mention that the custom was observed by Alexander in the Katheae region of Punjab. Importantly, neither of these historians saw it by themselves. They made these records on the basis of the narrations of other people who were probably eyewitnesses. If these records are authentic, then the practice of Satī goes back to second half of first century B.C. in case of Diodorus and 63 B.C. in the case of Strabo[18].

(Part 2: to be continued…)

———————————————————————————————————————

References

[1] From the texts referred to in this article, only the Rājatarañgiṇī has used the word Satī-

प्रशान्ते तुमुले बिम्बा चतुर्भिर्दिवसैः सती ।

तुङ्गस्नुषा सुता शाहेः प्रविवेश हुताशनम् ॥ (7.103)

Four days after the disorder had ceased, Bimbā, who was a daughter-in law of Tuñga and daughter of Śāhi, entered the fire as a Satī.

[2] The term Sati (short ‘i’) means the end or the destruction.

[3] तत्रैनं चितास्थं माद्री समन्वारुरोह | (The Mahābhārata, Ādiparvan 90.75)

[4] Let these unwidowed dames with noble husbands adorn themselves with fragrant balm and unguent. Decked with fair jewels, tearless, free from sorrow, first let the dames go up to where he lieth. (Ralph T. H. Griffith, Hymns of the Rigveda, 1896)

[5] Rise, come unto the world of life, O woman: come, he is lifeless by whose side thou liest. Wifehood with this thy husband is thy portion, who took thy hand and wooed thee as a lover. (Ralph T. H. Griffith, Hymns of the Rigveda, 1896)

[6] अवध्याः स्त्रिय इत्याहुर्धर्मज्ञा धर्मनिश्चये…|| (146.29)

While deciding Dharma, those who know it (Dharma) say that women are not worthy of being killed.

अवध्यास्तु स्त्रियः सृष्टा मन्यन्ते धर्मचिन्तकाः |

तस्माद्धर्मेण धर्मज्ञ नास्मान्हिंसितुमर्हसि || (206.4)

Those who ponder over Dharma say that women are not worthy of being killed so the one who knows Dharma (you) should not kill these (women) with Dharma.

[7] कूटशासनकर्तॄंश्च प्रकृतीनां च दूषकान् ।

स्त्रीबालब्राह्मणघ्नांश्च हन्याद्द्विट्सेविनस्तथा ॥ (The Manusmr̥ti, 9.232)

Forgers of royal edicts, those who corrupt his ministers, those who slay women, infants, or Brahmanas, and those who serve his enemies, the king shall put to death.

[8] History of Dharmaśāstra (Vol 2)

[9] संवत्सरं प्रेतपत्नी मधुमांसमद्यलवणानि वर्जयेदधश्शयीत || (2.2.4.7)

षण्मासानिति मौद्गलः || (2.2.4.8)

अत ऊर्ध्वं गुरुभिरनुमता देवराज्जनयेत् पुत्रमपुत्रा || (2.2.4.9)

For one year (after the demise of her husband), The wife of the dead should abstain from honey, meat, wine and salt. She should sleep on the ground. Maudgala-s believe that this should be followed for 6 months. Thereafter, a widow without a son may, with the permission of elders to procure a son from her brother-in-law.

[10] The Dharmasūtra-s are dated till 300 B.C. whereas the Smr̥ti texts can be dated till 300 C.E. The Mitākṣara, the commentary on the Yājñavalkyasmr̥ti can be dated to 1100 C.E. (History of Dharmaśāstra (Vol 2, Part 1)).

[11] There are references which forbid Satī for Brahmin widows, Aparārka quotes

पैठीनसिः | मृतानुगमनं नास्ति ब्राह्मण्या ब्रह्मशासनात् | इतरेषां तु वर्णानां स्त्रीधर्मोऽयं परः स्मृतः ||

Following (husband) after death is not for Brahmana widows due to the order of Brahma. For, the females of other Varṇa-s, this is known as the greatest Strīdharma (duty of a woman).

[12] Kane (1941: 626)

[13] इत्थं रतेः किमपि भूतमदृष्यरूपं मन्दीचकार मरणव्यवसायबुद्धिम्|

तत्प्रत्ययाच्च कुसुमायुधबन्धुरेनामाश्वासयत्सुचरितार्थपदैर्वचोभिः|| (4.45)

Thus, some being of unseen form discouraged Rati’s desire of seeking her death and through a belief in that the friend of the flower weaponed god (voice) spring, consoled her with words.

[14] अणुमरणपत्थिआए पच्चागअजीविए पिअअम्मि |

वेहव्वमण्डणं कुलवहूअ सोहग्गअं जाअम्||

(Sanskrit – अनुमरणप्रस्थितायाः प्रत्यागतजीविते प्रियतमे|

वैधव्यमण्डणं कुलवध्वाः सौभाग्यकं जातम् ||)

As she stood for the following death (of her husband), the ornamentation for the widow daughter-in-law of the family became her ornamentation of good fortune (married life) because of the returned life of her dead husband (because he came back to life, she did not go Satī.)

[15] He was sick and showed little to no signs of survival so his wife committed self-immolation prior to his death. This is recorded in the 5th Chapter of the Harṣacarita by Bāṇabhaṭṭa.

[16] यदेतदनुमरणं नाम तदतिनिष्फलम् | (This thing called anumaraṇa is absolutely unfruitful.)

He further gives examples of women who have not committed Satī.

अन्याश्च रक्षःसुरासुरमुनिमनुजसिद्धगन्धर्वकन्या भर्तृरहिताः श्रूयन्ते सहस्त्रशो विधृतजीविताः |

[17] अवरोध्यवधुमध्यात्सती तं पतिमन्वगात् |…(6.107)

पत्यौ मृते सपत्नीनां दृष्ट्वानुमरणं ततः |

दम्भेनानुमुमूर्षन्तीमनुमेने स तां द्रुतम् || (6.195)

[18] Jain (2016: 9)

Views expressed in the article are of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official position of Mimamsa Foundation for Indic Studies.

Author : Jui Mande

Jui Mande wrote this article during her internship at MFIS.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks